Your basket is empty.

In search of the absent mind

One of the curious things about getting older is the increasing intolerance of memory. Mine just refuses to have anything to do with anything it deems less than crucial, which, according to Libby, is just about everything of a domestic nature. Absent mindedness is often the default position of the overtly brilliant, it is supposed to indicate an intellect with much better things to do than remember its hat, or doing the washing up or its silver wedding anniversary. In the brilliant forgetfulness is rarely seen as a deficiency because the brilliant are always busy being brilliant, who cares if they forget where they left the baby if after misplacing it they cured cancer. I have tried the I’m too clever to remember argument on Libby and it has be said I don’t think I got away with it. I even attempted to convince her that baldness was symptomatic of brilliance as my head was so stuffed with ideas they were pushing the hairs out from the inside, needless to say her merely mentioning Jason Statham was enough to quash that argument. For the record though I think the Stath is a genius but in exactly the same way that David Beckham isn’t.

Memory is so easily misunderstood, we are most aware of it when we are called upon to remember something, the seven times table perhaps or our single line in the school play or pulling the hose out of the swimming pool so it doesn’t overflow into the pond and chlorinate the fish. For some people things just stick, for others it’s like their brain has been turtle waxed, everything runs off. I have always had to go over the humdrum again and again before I remember, I still don’t know my mobile phone number, luckily I don’t need to because Libby knows it. This tends to be the part of memory that stutters first with age, the part that suddenly compels you to check the oven is off and the front door is locked and makes you turn the flat over looking for the glasses that are in the pocket you patted just moments before setting off to look for your glasses.

Forgetting the mundane is annoying but little more than that, they are the memories that skim across the surface, not the ones that descend, rocking side to side, until they rest in the silt, deep and permanent on the bottom. These are the memories I cherish, the ones I don’t have to remember, the simply unforgettable. This is where we keep all of what makes us who we are, the importance of being, the notion of love and the illusion of time. It is our sense of mortality, morality, of loyalty of preference. It is the promise we make in haste, the heart we carve in a tree, the decision we cut in stone. It is the gap between the truth and the recollection, the tune that is more wistful when unexpected, why the return home always seems shorter than the outgoing journey. It is all the dust and sparks, the embers and the ash, it is all that we hold and hold dear.

It is why nothing seems crueller than when the unforgettable is forgotten, when the treasured past goes inexplicably missing. The mind returns to the right spot, it knows where it left the memory, the time the place, only to find the landscape dragged smooth. The self flutters for a moment, craving the answer to the question but remembering only that it has lost something. I have seen this happen too many times now, the creeping confusion when nothing comes to mind, the slow climb back up to eye contact, then watching as the act of forgetting is forgotten to be replaced by an uncertain smile. Dementia is much more than the loss of memory, it is the loss of love, of family, of future, it is the severing of the tether that connects us to our very existence. When losing our memory faint recognition feels like a lie, familiar faces merely remind us of someone else. We become impermeable, drifting through the depths of inner space, while slowly but surely the stars in our universe wink out, leaving only darkness and unimaginable distance.

Terrible as this is it is often worse for the forgotten than the forgetful, when the child becomes the vessel of the parent, their living repository. Once shared recollections become singular, definitive, and the ties that bind are unbound, communion withdraws until conversation feels like shouting through the letterbox of an empty house. We stare into the faces of loved ones, appealing for a clue as to their whereabouts, searching behind the eyes for a flit of expression, some trace of the truly absent mind but are left only with a guilty sadness and the unwanted sense that they have abandoned us.

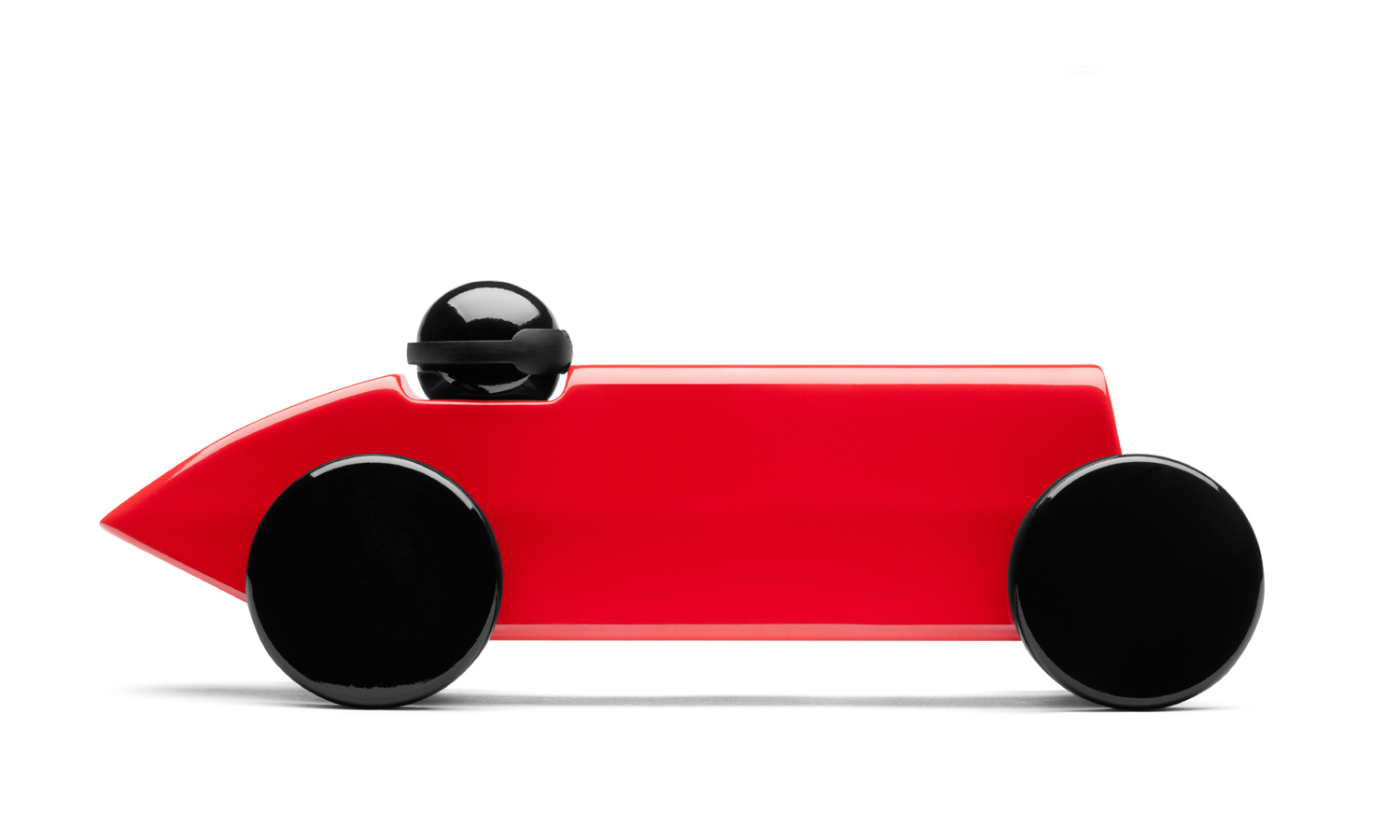

Within ourselves we fear for the same fate, question simple lapses of concentration, anticipating a loss of cognition while we are still able. Yet these internal considerations are as nothing when compared to the attention we lavish upon the external, as if forgetting our bodies are little more than elaborate vehicles, beautifully complicated transport, uniquely liveried carriages for the mind. We confuse our dazzling exteriors with our inner selves, maintaining and admiring the paintwork, often quelling the occupant to extol or photograph the superficial. Yet it is the depth of our memory, the quality of our reason that lifts our head and lights our face, that shapes the thoughts that animate us, that makes a photograph worth keeping and a moment worth remembering.